Other people, so many people, would offer so many reasons to nominate Dr. Ray Herber as the most unforgettable character anybody could ever meet, but for me it’s his voice. Masculine, bass, mellifluous and resonate but not special-effects ghostly; strong but not rock-splitting or platoon-flattening; measured but not drawling; magisterial but not imperial; professorial but not puffy. Even-toned and controlled but not robotic; never raised in anger, hardly ever raised at all; never heard haranguing doctrine or politics, unaccompanied by gesticulations, silent to gossip, shorn of scurrility, interjection, even exclamations. Unflappable. Coaxing, compelling, subliminally mesmerizing, a hint of cajolery and a whiff of a whiff of some middle kingdom accent. And a barrel of wryness, wit, and drollery, that’s obvious, and if rollicking comedy is in it, you suspect it is, it’s hidden. His voice is Mosaic, his face is Mona Lisa’s. His is the voice of the Sermon on the mount, not the altar call; the bewigged judge, not the activist or prosecutor. The tuxedoed by-appointment-only Beverly Hills art gallery broker, not the auctioneer, or circus barker, neither a TV evangelist nor youth minister, more like an undertaker. The voice-over for the Lone Ranger or the Buckingham Palace telephone answering machine. Your captain speaking about a little problem with the right engine. Or your doctor speaking.

It was as a disembodied voice on the phone that I first encountered him, about 20 years ago. Octogenarians now, both he and I graduated from Loma Linda University School of Medicine, I in 1953, he in 1957, but I’d never heard of him before 1993. I was working in Dayton, Ohio, as a pathologist, when out of the blue, actually from Loma Linda, California, this stranger phoned me. “I’m Raymond Herber, class of ’57, calling …” for an instant I didn’t catch what he was saying, so enthralled was I with the voice, but eventually I caught the drift: “… rummaging through some old storage crates here at the Alumni Association and … I happened across a collection of old drawings and caricatures you drew, your name is signed to them, of the faculty, 40 years ago. They’ve been stored away all this time, lost and forgotten. But they shouldn’t be – they’re exciting.” No exclamation mark. He didn’t sound particularly excited, but I was -- I’d long ago given up trying to find out what ever happened to those drawings. The voice went on to say that the Alumni Association (actually Dr. Herber personally) wanted to publish the caricatures as a book. And they were (Giants of CME, 1994), at Dr. Herber’s own expense, through the Association, as I learned – by hints, inferences – only recently.

Thus it was that Ray entered my life, not merely as another acquaintance but to change my life, as he has so many others. Our relation, however, has been unique, being through art projects, for the Alumni Association – faculty portrait galleries (a series of >60 oli portraits)https://www.llusmaa.org/page/faculty-portraits, large commemorative paintings, and another hardback another anthology of the paintings in color that he also published and financed. As a team, I have done only the easy part, the painting, while he has been the brains and done the heavy lifting, as the art director (suggesting the subjects); agent (selling the administration on the projects; arranging and scheduling posing sessions by faculty members); funding covertly and indirectly, of supplies and frames and publications; and personally hanging the paintings on various walls, back in the days when an array of bureaus and committees, or the EPA, didn’t have to give approval. Without him I would simply have painted, unnoticed, forgotten, as my old caricatures were. Thanks to him, I became a virtual professional portrait painter and achieved my 15 minutes of niche-fame.

It was as their physician, a professor-physician, that so many patients have heard him informing them, always with the same comforting voice, that their tests are fine or that chemotherapy will be necessary, phoning them after hours to see how they are, or that they can show their gratitude – he has a way of generating endless amounts of it: he’s the very doctor you like and want to keep, in your dreams – by a gift to the medical school, though the Alumni Association. Through channels, is how he operates.

Dr. Herber has been the voice, and the vision, mighty voice and mighty vision, of the Alumni Association, for almost 60 years. As president, activist or adviser, unofficial or official, self-appointed or drafted, he is heard in personal conversation or staff conference, every possible committee, or black-tie event, usually not at the head table, always urging more efficiency and a stop to all this waste. “We must have a plan.” Ringingly he argues in behalf of all the official undertakings, especially if involving money and budgets, such as funding student tuition, and sundry other projects all over the community, monumental and trivial, mostly of his own creation, so many and diverse nobody can keep track of them. He puts his money where his mouth is, not only into all the official things he promotes, but also into his own personal funds and unofficial personal projects only he contributes to, or knows of. With such interest and expertise in dollars, he should himself be rich, awash in portfolios and dividends. He isn’t, apparently. He is not your average rich doctor, holed up in a gated community. His own wealth -- only the IRS knows what it might be -- he has redistributed, covertly, steadily, effectively, to where his heart is: the school, other people's comfort.

Most famously the Herber voice is heard in behalf of endowed professorial chairs, six for the Department of Medicine and two for basic sciences, suggesting and designing them in detail, from inspiration he has derived from his monitoring other universities, and campaigning to get them financed. This is accomplished not at banks of microphones and video cameras and strobe lights or barricaded rallies or galas, but by one-on-one encounters, like ours back in 1993, starting with his colleagues, thousands of them, whether doddering retirees making out their wills or still gowned graduates tossing their caps into the air.

His message is that we physicians, of all people, ought to be supportive of our medical school, not only from gratitude for our own education and earning power and place and purpose in society and in the church, but also to further our university’s mission and heritage, wherein lie our own identity and confidence, thus to train ever more physicians, thus to further enrich our own heritage and impact, forever. Mercifully his pitch is innocent of the argot of media relations consultants, like, “Join hands with all your friends in our shared metonymic dream! In compassion extend your hands and heart in outreach to the globe, soar boldly into the sky! Maximize an innovative cognitive transforming course in health education, help us empower the change you can believe in [oops, that one is already taken],” or I’d hang up on him. If sometimes with annoyance, his message is heard, checks written, almost a hundred million dollars’ worth.

The man gets results, and expects results from those results. From beneficiaries, whether students or endowed professors, he expects productivity, and soon, with proof, written reports with graphs. If not, the settled voice comes the closest to rising.

The voice has been heard all over at the campus. Back at the faculty medical office, across the street from the university, he didn’t merely practice medicine but also organized, administered, and served as president of the incorporated faculty group practice. Though nominally retired, just recently he was heard advocating rules, historical but now shockingly novel, such as that new patients must be seen within a week; phone calls from patients still must be returned by doctors, not assistants, and wouldn’t it be a good idea to have local retired practitioners do housecalls? Alas, not even he can win them all.

At the university he still regularly counsels the dean, calling attention to, among other things, how it is done at Harvard. Next, he is censuring the President and the CFO for the calamitously increased debt, his finger tapping the rocketing regression line on one of his hand-plotted graphs, for which is as famous as Karl Rove and his hand-held chalk board.

As professor (now emeritus) and vice chairman of the Department of Medicine and Chief of Gastroenterology, creator of the gastrointestinal fellowship, in his research laboratory (focused on lactase deficiency), his cadenced voice is heard bandying homespun mottoes and proposing no end of progressive schemes, but never political machinations, and in teaching.

He loves to teach, apparently as much as he loves budgets. From lectern to bedside, he teaches. He tells me that he prefers, and likewise, I suspect, the med students, one-on-one bedside teaching to lecturing in the amphitheater. His buttoned down, necktie style may not nowadays generate, I suspect, 5-star evaluations from students accustomed to frayed jeans and hectic Power Points and being addressed as dudes.

Maybe so, but the award committees have run out of plaques for him, to his delight and relief. However, if you do something honorable, he’ll demand and connive unceasingly that you be publicized, plaqued, and banqueted, and, if you live far away, flown in for the occasion, ostensibly at the university’s expense, actually his own. By nature, not out of mindful obedience to the Biblical admonition, when giving his alms the public left hand ready to hoist the heralding trumpet and microphone, rarely knows what the private right is doing. Normally a master of clarity, he becomes a master of murk when he is queried about his own eleemosynary activities. By filling in the dots I have recently caught on to how a few years ago he got the notion that older grads should be lifetime Association members, and if they weren’t already he himself would pay for them en masse. Many old grads are discovering they are members, courtesy of “anonymous.” I suspect this may be the tip of the icing on the tip of the iceberg.

All this is unique to him. He is non-mainstream. So it seems fitting that he should have other, some would say, eccentricities. He’s a collector of dolls, antique, period, rare collectible and truck-stop souvenir, tiny and life-size. Like kudzu, but in a manner as organized as the Association's budget, dolls have taken over his house (a respectable medium-size house in a middle-class neighborhood), every room, every wall (dolls packed in ranks like the crowd along Colorado Blvd at the Rose Parade), every sofa and chair, every horizontal plane except the 3 shelves reserved for his famous collection of 3-ring notebooks stuffed with newspaper clippings and data and graphs. And if dolls have taken over his house, he and his wife have taken over organized doll-dom. He has been president of the regional Doll Discovery Club. Somehow he winds up as president or on the board of every organization he gets near – local medical society, boys choirs (his son sang in one), music societies, zoos, colleges, doll clubs. Whatever organization he's involved with will want him as president and he will accept so that he personally can see to it that it functions effectively. High office in state or national or international organizations he does not aspire to, for they offer mainly celebrity, which is what he sees as eccentricity.

He has always done needlepoint – naturally he would, with his attention to detail and precision -- exquisite, I would have to say awesome, until his thumbs got arthritic, whereupon he simply began to paint, taking up where I left off, copying – are we surprised? – twenty million dollar Picassos.

Likewise, the copious illuminated scripts and graphs that famously accompany his verbal presentations are written and plotted by his own hand, as fastidiously as his needlepoint, as laboriously as a medieval monk copying the Apocrypha, always have been, always will be. With a gentle but categorical huff he dismisses quill-replacing devices, notably computers, anything with a screen and a pixel and a cursor, even the navigation screen of his leased fire-red Mercedes. It’s not that he couldn’t, he won’t, absolutely will not. He’s making a statement, is my guess. He doesn’t suffer fools lightly and what is the web if not a ship of fools? A real friend, not a virtual facebook friend. Nor does he do eMail. Better, he’ll phone you, even if you live in Ohio, or Holstein. As minutely helpful as he is thrifty, he has kept church bulletins to deliver to shutins every week for half a century, and probably still does even though the services are televised.

A man of medium height and unprepossessing build (like me), an ethnically pure German whose line of farmers and craftsmen (it must have included Bismarck) emigrated from Holstein, Germany, at the invitation of Catherine the Great, to the Volga region, and then on to Oklahoma, where Ray, one of seven siblings, grew up on a farm, milking cows, no doubt endowing the chairs and budgeting the alfalfa, and still speaking German (hmmm…so that’s what that hint of a whiff of an accent is). From the farm he moved on to be valedictorian in grade school, high school, and college, and top man of his medical school class, among the top ten in the nation in national exams (“National Boards”), and then a research fellow (gastroenterology) at Washington University School of Medicine.

So there he is, just off the phone, standing before you, arms straight down, wearing a loud Hawaiian shirt, softly smiling, softly suggesting some dynamic new scheme. There it is, my portrait of Ray in words, plus surround sound.

This portrait is photorealistically accurate, but I’m afraid it has come across as more of a smiling caricature than the sober panegyric this iconic figure deserves and usually receives. But my writing, long of face at the beginning, always comes out chuckles, the more so the more into my subject I am. In this case it's OK, as Ray, who was allowed to read this before publication, has assured me. It turns out -- you need to know us pretty well to discern this -- both of us are furtively jocular sorts, especially squirmy in the limelight.

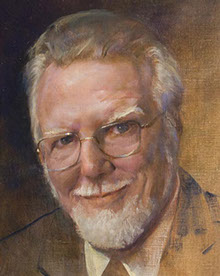

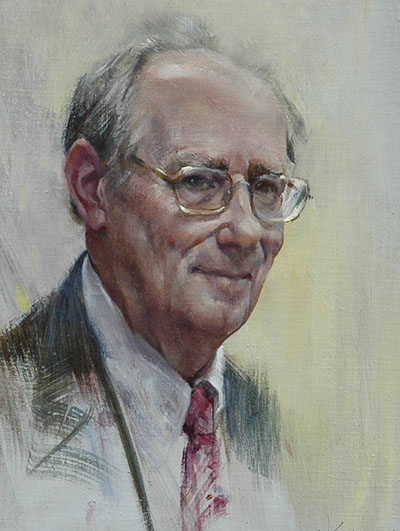

Ray is indescribable, which may describe him best. To get closer to his essence, and to more respectfully convey his qualities, a more stately mode is required – a painted portrait. So I also offer a visual portrait of Ray, oil on canvas, painted in 2002, when he stil l had dome hair (see above). Only visually can you begin to grasp the gentleness of the man, the composure and contentedness, the confident inscrutability. Extreme emotion is not all that difficult to capture on canvas, take it from me; subtlety is. As a portraitist, I have never before, or since, encountered such an challenging, elusive face. Leonardo di Vinci saw it, in Mona Lisa, and managed to capture it, almost. Not even a classical portrait can, totally. So I’m back to caricature, which is where we came in, 20 years ago. Too bad di Vinci didn’t do caricatures -- he was busy drawing flying machines.

l had dome hair (see above). Only visually can you begin to grasp the gentleness of the man, the composure and contentedness, the confident inscrutability. Extreme emotion is not all that difficult to capture on canvas, take it from me; subtlety is. As a portraitist, I have never before, or since, encountered such an challenging, elusive face. Leonardo di Vinci saw it, in Mona Lisa, and managed to capture it, almost. Not even a classical portrait can, totally. So I’m back to caricature, which is where we came in, 20 years ago. Too bad di Vinci didn’t do caricatures -- he was busy drawing flying machines.

Portrait of Ray