Monet vs Modernist

Which is which?

Monday, June 2, 2014

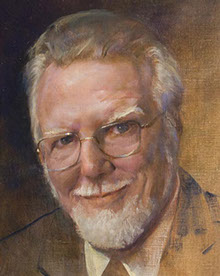

Being an artist myself, I’ve always been especially fascinated by modern art, and, more recently, Modernist Art, separate fields, as I see them. So that’s what I’m writing this essay about, modern and Modernist Art, from a perspective so personal that this will be more of a memoir than a scholarly or even informative discourse.

Modern art I like, having grown up with it and happily applied some of its styles, techniques, and principles at my own easel. I consider myself a generic realist painter, just slightly impressionist rather than photorealist.

Modernist Art is a different story. I see Modernist Art as modern art gone a little crazy, then frankly wild, then berserk and run amok, winding up as an entirely new genus (Modernist Art, capital M, capital A) to be distinguished from modern art (small m, small a). And for my purposes, to be distinguished, without discussion, from Postmodern Art. So, on the great Evolutionary Tree of The Art Kingdom, Modernist Art must have its own branch separate from modern art. A private classification, mine, unknown beyond this unknown web site.

I was eight years of age when I first became aware of modern art in the form of architecture. That was in 1937, in the pioneer days of the San Fernando Valley, then populated only by tumbleweeds and scrub, or, in North Hollywood where I grew up, apricot orchards.

My parents had cleared a small lot and themselves built a smallish house, at the time the first and only house on the block among the apricot trees. I can still see that house in my mind’s eye. It was of defined style, the California-Mission, earth-colored adobe and mortar squeezed out between the courses, huge antique ceiling beams, multi-gabled terracotta tile roof, and all. And I see my dad, shirtless, tanned, antiquing the giant ceiling beams with an unwieldy, smoky kerosene blowtorch.

And I can still see in my memory the residential styles that prevailed back then (there weren’t many commercial buildings yet). What predominated were the California-Mission and Mediterranean styles. Our adobe casita fit right in. I suppose I was rather young even to notice architecture, but I did, as omnisciently and smugly, I thought, as the L.A. Times Architecture Critic.

Then one day my world changed. On the smallish lot just across the street from us the apricot trees were cleared out and an eye-poppingly alien structure, it seemed to be a house, materialized. Smallish like ours but otherwise absolutely opposite: L-shaped rather than bunched up, the longer wing nothing but glass, the shorter a blank very white wall with a string of slit windows along the top edge; naked of window or door molding or beams, altogether as stark as a slab, simplified to the bone; roofless, as near as I could tell.

When I was older I realized that that house must have been designed by an architect, an extraordinary one. I wondered who. I had learned about Richard Neutra, famous for bringing box and glass to the L.A. area. and suspected him. A few years ago I researched the architectural history of Southern California, and confirmed that the architect of that certain house was indeed Neutra.

A young Austrian recently trained in the radically modern architecture then emerging in Europe, Neutra had emigrated to America. Landing in Chicago along with fellow expatriate architects like Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, who stayed put and became world-famous (they designed huge buildings), Neutra moved on to Southern California to become an icon of local architectural history (he designed residences mostly). Neutra was essentially unknown in the East, which then regarded Southern California as backwoods. Built, according to the archives I found, in 1937, which is how I know I was 8 years old at the time, that house across the street was one of Neutra’s earlier commissions, possibly the smallest.

At about the same time as Neutra was dropping my jaw and opening my eyes, I was introduced to painting. As it turned out, it was a sort of modern painting that I first beheld.

The 1930s was the Golden Age of California Landscape painting, definitely “modern” and quite different from the earlier kind of “classical” American landscape painting of, say, the Hudson River School and Frederick Church and George Inness, beloved, even awesome, and very dark.

California Landscape painting was already legendary, at least in Southern California if not the East. Legendary California landscapists such as William Wendt, Granville Redmond, Guy Rose, and Edgar Payne, were regularly exhibited in the long-gone art wing of the Museum of History Science And Art in Exposition Park in Los Angeles. I remember being taken there, often.

Those California landscapists were not just hobbyists or amateurs who happened to be in California and had taken to painting because California was so paintable. Immigrants from Europe, like Neutra a generation later, or Americans who had studied art Europe or at academic centers in New York or Pennsylvania where the teaching was strongly influenced by new European art, they were professionals well trained in the newly emerging European then modern art, notably Impressionism.

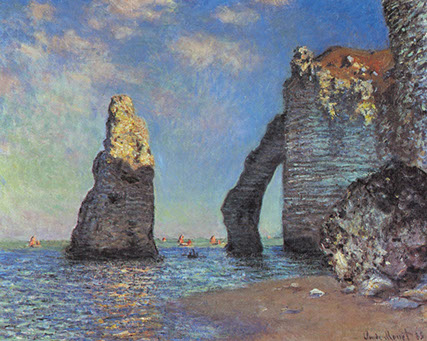

Historic Impressionism is a particular school of painting defined by its peculiar technique (careful dabs and short sharp strokes); style (loose yet deliberate); subject matter (lily pads, provincial villages, hay stacks, pastoral scenes, shimmering ocean); lighting (twilight, fog); venue (plein air); palette (more saturated colors, no black); and its sainted charter members (notably Monet, Cezanne, Sisley, Cassatt, maybe Renoir and Degas).

The logo of Impressionism is the dab, Monet’s trademark. I didn’t say “daub.” Dab and daub are not the same. Both being a sort of jabbing action, a “dab” is done carefully, fastidiously, to achieve a specific effect, while a “daub” is careless, thoughtless, messy. Experts are careful with the words; bloggers aren’t.

But what defined Impressionism most crucially – please take note; hardly anybody does -- is that it emulated realism, as classical painting always had, but more realistically through newly appreciated optical principles and new ways of putting the paint on canvas, while – please note this too -- adhering strictly to expert, academic drawing and proven principles of realistic perspective and proportion.

Throughout the ages painting had striven to achieve reality, certainly in landscape painting, by striving to replicate on canvas, when viewed as close up as a jeweler repairing a watch, the exact color and shape and detail of tree and leaf, but usually wound up tedious, blackish, and boring.

Impressionists didn’t so much as try to mix exactly the right color but used two or three complimentary or secondary colors applied to the canvas as adjoining dabs. Nor did they try to reincarnate the precise shape or total detail on canvas. Nor did they want the viewer’s nose in the canvas. Instead they told him to stand back about ten feet, and relied on a viewer’s brain to take over and process the image to give a perception of realism greater than from classic pickiness. Impressionism strove for reality not through cloning it but through certain quite scientific if serendipitous techniques for obtaining only an “impression” of reality, to be transformed by the viewer’s brain into consummate reality. Viewed up close, a mess; viewed from a distance – viola! reality! Dabs, short strokes, and viewing distance worked the magic.

Those are obvious and crucial characteristic of the virginal Impressionist movement at the turn of the 19the century, and crucial to understanding the difference between modern and modernist art, but for some reason utterly ignored by the academic art world.

Nowadays Impressionism is proclaimed the watershed in art history, a whiplash u-turn from reality to creativity, as revolutionary as the French Revolution and as bloody; the Mother of the mob of narcissistic Modernist Art prodigal sons that have disgraced their mother and her purpose – to honor reality -- and taken over art history and overrun the planet like kudzu.

But classic Impressionism also spawned a handful of unsung painters who have honored reality and fulfilled the Impressionist promise. Inspired by the Impressionist goal of achieving ever stronger reality, but not doctrinaire about the totemic dab, these painters have quietly taken to new methods and strokes foreign to Monet.

Whereas the prodigal Modernist Artists never experience a mutation without a press conference to announce another break-through brand name -- Cubism, Pointillism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Abstraction, Transgressivism, Absurdism ad infinitum – Impressionism’s humbler more honorable progeny never bothered, nor, rather surprisingly, did the quick-to-stigmatize academic critics, nor have art historians.

Call them generic impressionists, or simply impressionists (small i; fittingly, the i is not the big I), as distinguished from classic, historic Impressionists (capital I). That’s how the famous California landscapists as a group are known –- “California impressionists,” – while individuals may defy classification altogether. Sargent himself was actually a pretty venturesome impressionist (small i), especially in his watercolors and oil landscapes (not so much his commissioned portraits). But on one hand Monet wouldn’t recognize Sargent as part of the inner circle because Sargent didn’t go all out for dabs. On the other hand, haute critics demonize him for not going all out weird. Sargent left it to Picasso to put three eyes on one side of a head. Among current practitioners of decorous impressionism are Richard Schmid, Matt Smith, and Ruo Li, credits to their line. Though not displayed at the MoMa or Saatchi gallery or the Frieze Art Fair, they are my personal heroes.

The basic and underlying, the founding principles of modern art, as demonstrated in Neutra’s modern architecture and the California Landscapists’ impressionism, are as follows: mass and shape for their own sakes; simplicity if not starkness, devoid of rococo; a degree of looseness and “lack of finish” (as 19th century academic painters disapprovingly saw Sargent’s portraits) rather than obsessive punctiliousness; asymmetrical balance; the use of technique to serve the effect but not to demean reality. As pictures hanging on a wall in a Neutra house, a playful abstraction or a Paul Klee are as suitable as, or arguably more suitable than, a Bougeraux or Norman Rockwell.

A brief shining moment in the history of modern painting, Impressionism (capital I) began with a bang in 1863 when Manet (not Monet) was first exhibited, and ended with a whimper in early the 20th century when the dab evolved and mutated into daubs celebrated as strokes of genius, liberators from classical enslavement, awarded as the new culture, bowed down to and apotheosized for their own sakes, as new gods. Of draftsmanship and perspective Modernist Art was contemptuous. So as not to compete with creativity, Reality came to be presented only as essence, or ignored, or forgotten; rejected as mundane, vapid; unimportant compared to novelty; even ugly, somehow capitalist, to be despised and caricaturized.

To better serve reality, Impressionism had empowered the literal eye and the brain. Confusing dimness and distortion with creativity, Modernist Art pithed the brain and plucked out the literal eye, and empowered the Inner Eye, which can’t claim to see anything but fog.

Alas, Modernist Art didn’t stop evolving and degenerating. Having trashed the literal eye and magnified the Inner Eye, it grew a mouth and wagging tongue that itself grew and grew and took dominion like the “little horn” of Daniel 7.

Throughout history artists had, as craftsmen, served, sometimes obsequiously, the establishment, whether religion or a government, or mythology or the prevailing idea of beauty, both famously Greek. No longer! Artists arise! Artists of all species, notably heroic composers and poets in the Romantic era and filmmakers and movie, rock, and rap stars in our social media era, have cast off the role of servile craftsman and mere entertainer and taken unto themselves the crown and diadem of emperor, the mantle and beard of prophet, shaman, oracle, and the wig and robe of supreme magistrate of all culture and all morality and all justice, social or otherwise, even…truth. And that culture and morality and justice, and truth, is somehow utopian Marxism. So the enemy has to be capitalism and founding American democracy and established values, to be depicted as ugly pigs, black-haloed and purple, or simply as a collage of blobs, and their victims as shrieking, bloodied, naked, with texting and graffiti to leave no doubt.

Art is no longer art for art’s sake but art for the agenda’s sake. Liberated by modern art, Modernist artists have become slaves to ideology. Simperingly, docilely, Modernist Art goes wherever ideology leads it by the nose- or lip-ring, while claiming that it goes where no man has gone before. That last part is all too true.

The millennia of slow, tedious, intelligent progress in painting has been reversed, derided, purged from our culture, end of debate. A surprising amount of cave art showed more craftsmanship, drawing skill, aesthetic and common sense than Modernist art does. The Dark Ages of Art, proclaiming itself the Liberated Age, now now enshrouds us. Future art historians will scratch their heads. Manet and Neutra would ....weep .