My

Retrospective Exhibition

Thanks to perspective, Professor Ted is the largest figure in the picture, on the right

Photo by Leslie

rewritten Thursday, November 16, 2017

An Octogenarian

Artist's Statement,

...twice!

For the gallery wall at my one-man retrospective exhibition in 2016 entitled “My 87-year Life in Art” I was asked to write an artist’s statement. I wound up writing two very different ones. One for the wall, one off-the-wall.

The exhibition was held at the university whence I had graduated in 1948. Back then a biology/premedical major, I was at heart an artist but didn’t know it. The closest I came to taking art classes were two electives, one in Renaissance History and another in mechanical drafting (some day I was going to build and design a house, an arty one).

In my day the place was merely a small Bible college with only a token art department. In 68 years since then it has evolved into a sprawling modern university with a culture and theology to match, even for the schools of religion and biology. And of course the art department, now boasting of an impressive art building, more art majors than we had biology or theology majors, life classes and all, and a splendid exhibition gallery with LED track lights that actually focus on the right places on the walls, funded by (and named for) an elderly much esteemed affluent patron. Under the direction of a young, curiously attractive, thoroughly modern curator named Ted, a very conscientious and professional curator who personally installed the LED lights and focused them, the gallery has seen only modernist exhibitions, quite good ones, I’ll have to say. But the patron decreed there should be at least one realist exposition, mine.

Obediently, Curator Ted first off informed me that an Artist’s Statement posted on the gallery wall is standard part of gallery culture nowadays. Likewise standard the content of the Statement. And rather in detail he warned me that the Statement must not offend prevailing values. I’m not a big fan of prevailing values. Dr. Ted must somehow have gotten wind of that.

I’ve been a student much of my life and I know how to cope with professors. Give them what they want. So I belabored a token statement that while it failed of the sort of rhapsodies Ted likes, was as inoffensive as Saturday’s progressive sermon. Honed to the bone, it is as short as anything I’ve ever written, even though I tucked in a bit of faint praise of modernism – my definition of it. Professor Ted, my new best friend, heaving a sigh of relief gave it a passing grade and posted it.

That done, I cast off my academic robe and blue jeans and forthrightly returned to being a bearded old codger, my true persona. Back to the keyboard I went. For nearly a year, through most of 2017, and into my 88th year and over 80 versions, I struggled with a Statement that had been rattling around in my mind for a lifetime and that would satisfy me if not Curator Ted, or any curator. It’s way too long for posting on a gallery wall, even a little long for posting here.

Anyway, octogenarians like me don’t write artist’s Statements. They do memoirs or autobiography, whichever, the difference is subtle, and dictionaries can’t keep it straight. As it happened Curator Ted also required me to write one, and I did. He specified that it be written in the third person, making it a “biography,” neither autobiography or memoirs. But it’s posted on another page, so let’s get down to business with The Statements.

POSTED VERSION: ARTIST’S STATEMENT, SUITABLY NEUTERED

To summarize, I just do it.

In "just doing it" I have discovered that when drawing or painting either portraits or plein air landscapes, whether sketches or finished paintings, I am comfortable in pursuing verisimilitude and detail in the classical realistic style, usually rather tightly, sometimes loosely. If I have a role model he is Singer Sargent.

On the other hand when I have had occasion to design a house or pursue a sculptural project, I have favored a generic, “timeless” modern style, which I define simply as nonideological simplicity as an end in itself.

OFF-THE-WALL VERSION: CRUSTY OLD ARTIST’S STATEMENT

I started my long journey in art just doing it, without ado. I never heard of an Artist’s Statement until I was half way through my life. Even as a small child I was taken to galleries and painting exhibitions, but if there were such things as Statements, I was so eager to get to the paintings, and so young, that I skipped the printed stuff.

But now I learn an artist’s statement posted on the gallery wall is as crucial to the exhibition as klieg lights and a Lucite podium to a church.

Fine. So where do I start? Left to my own devices, I would begin with questions I’m asked. Actually, I seldom get any. About the only one I remember is, “How long did it take you to do that?” Answer: it varies. Next question? “Exactly what do you mean when you say you ‘just do it, without ado’”? To my surprise and disappointment, that question nobody has ever asked. I suspect that for most people “I just do it” doesn’t really say anything. Actually, it does and I’m eager to explain myself.

It sounds like something said by, or of, a genius. But “just doing it” is not necessarily as singular as it sounds. Is it not true of every dewy newborn power, from making art to making out, from making protests to making a difference? Touted as the age of idealism which implies depth, youth is in fact the age of mindlessly just naturally doing it. That’s the way I, and most kids born into religious families, do their religion.

As to “genius,” I prefer the term “instinct.” I suspect most people would laugh at the implied synonymity, for every last living creature, even plants, have unnumbered instincts. In fact, amoebas possess only instincts, thousands of them. And every last whale and human baby just does it, head for the nipple, without ado. But certain basically untaught instincts for higher functions like perfect pitch, painting, or mathematics are possessed by only rare individuals. That’s Genius. I seem to have such an instinct for art. (That’s not much comfort, considering that in other areas, like math, I’m preternaturally dumb.) That’s what I mean when I say that I just do it. I do make decisions – what size or shape canvas, what medium, brush, colors to use – but having decided the preliminaries, the painting part is frequently, not always, pretty nearly subconscious. I’m just doing it.

And from infancy I never thought about not having to think about it. It was when I became a man and was clobbered by philosophical polemics and downright scoffings that I gave some thought to doing it. In the case of religion I suffered scoffings for not being progressive and in art not be a modernist. Thus assailed, I awakened and responded with huffy if reactionary rebuttals. My art arousal occurred upon retiring from medicine when I segued into the fulltime study of art as intensely as I had studied medicine a half century before, but not as a just-doing-it student focused on passing tests but a scholar sensitive to, eager to pounce upon, issues.

Now I can see why professor Ted requires more than a simple “I just do it.” (not to be confused with a simple “I do.”)

I gather that The Modern Statement undertakes to tell the viewer what the heck he or she is looking at, -- the otherwise meaningless stripes dripped or rolled upon an expanse of canvas the size of a 2-car garage door. And the artist shares what she or he was thinking during the creative process, his or her ascents or descents into the heights or depths, in detail probing his or her feelings, culture, aspirations, experience. Finally, and clearly the most meaningful thing the Statement does is to proclaim to the cosmos and suburbs sundry standard socially and politically obsessed cryptic or blatant messages

Such transports reflect what modernism has turned art into. If I once thought art was merely bandying brushes, and for me still is, I’ve learned that for much of the art world, or more accurately the parallel universe known as modernism, it’s more about brandishing concepts or swords or flame throwers. It’s about fulfillment, consummation, communication, or that old favorite, the soul.

Rarefied modernist theoreticians expound the myriad of ferments, doctrines, and dogmas that comprise the criteria for pontificating ex cathedra and infallibly what art is and is not. It’s not what I thought it was. Or Rembrandt or Monet for that matter, I venture.

Thus a mystic creativity, sensitivity, spirituality has been bestowed upon modernist art. The philosophy if not the actual painting or pile of sticks has taken on a life of its own that transcends, and is liberated from, mere brush and canvas, marble and mallet, or skill. Liberated from the easel and plinth like Plato’s soul liberated from the body by death, mystic creativity, sensitivity, spirituality waft off into the vaporous cosmos, there to generate social and political and spiritual messages, mostly Marxist, that shower back upon the earth like comets or confetti. A painting is not an end in itself but a megaphone for messages, inevitably political, inevitably Marxist. Art is about the human condition, even saving the planet, and so on.

More frankly, art is the frisson of agony and ecstasy, your inner agony and angst and that of the cosmos. It’s about reaching out to, or outraging, others, or naught but a happening or event. Art is a pleasant way to make an income or as an excuse not to, or kill time or, not so pleasantly the bourgeois. But here’s what the prevailing-value Statements hope you never figure out: art is about generating fame, patrons, clients, agents, income, proudly or shamefacedly, and likes on facebook.

The breakthrough that enabled this apotheosis of the metaphysics of art has been evolutionary mutation of the literal eye into a vestigial organ, like the appendix or dewclaw, condemned for suppressing the vital inner creative forces the reside in the Inner Eye, apotheosized and duly capitalized. So the literal eye, undeserving of capitalization, has atrophied, or been plucked out as per Matt 18:9, for the same reason therein given. Thus liberated, the artist or art theoretician commune directly with the Inner Eye (and through the Inner Eye to the whole universe) to divine not a he or she but his/her/its essence, which turns out to be consummately ugly a la Rouault, or as whimsical as philosopher Picasso's three opaque fish-shaped eyes on a fish-flat face. Not picturesque humankind, but the human condition as Hollywood and novelists show it and original sin as orthodox theology annunciates it. Not a man’s nobility or a woman’s beauty, but humanity’s dehumanizing oppression by fat-jowled cigar-smoking capitalists, orange-haired freaks, and the pig-nosed cops, is discerned and inversely glorified. “Celebrated” is more familiar on the street or at galas.

Inner Eye art is a burgeoning thing, like a fungus. The latest art-fungus I’ve had the nerve to poke at (it’s actually about 20 years old now) transcends any specific message and is meant to be a free-standing art form just for the shock and awe and heck of it, chugging out chemically pure offal, obscenity, and blasphemy as putrid, corrupt, revolting, and downright evil as human creativity and spirituality can concoct, even with herbal, pharmaceutical, and satanic assist. As close as the most celebrated of these trolls, er, geniuses has come to stooping to the mechanics of visualization is the employment of every body fluid as media, readily at hand, and as pigment real clotted blood (real? what’s with this sudden urge to realism?), rather than Winsor Newton synthetic alizarin, which you will send off to Jerry’s Artarama.com for. But the designation of this sucker-punch movement is whimsically anticlimactic, rather as an overnight fungus looks like a cute animated Disney icon: “Transgressive Art.” Drug companies come up with more creative names for pills than that. Ask your doctor (please, not me). Mercifully, like a rare lethal fungus hiding deep in the woods behind a fallen tree, or in the Saatchi Gallery, it is unknown but to a nidus of exoterati and a handful of curious Googlers hellbent on discovering to what evil extremes such “art” can sink to.

As universally known as the nobility of patriotism or the righteousness of the heart of the saint once was, is the new paradigmatic persona of the artist as constitutionally psychotic or worse, much worse. Being cultured and civil, and only a dilettante at fine wine and mythology of antiquity, a Sargent could never be a true artist even if he daubed like a certified crazy. Van Gogh is the historic poster boy but wholesome compared to the “transgressives.” I’m as non-mainstream as anybody I know personally, but I doubt that the only the depraved, degenerated, drugged, destructive, demoniac, suicidal, haunted, troubled, or otherwise bad asses are eligible to be true genius artists.

I’ve heard it put without the boiling over I’ve indulged, and nicely boiled down. It was at a “demo” by a E.J. Robinson, a fairly famous realist seascapist. After splashing in a loose preliminary layer he turned to the audience and took a minute to announce that “If you stop at this point, not possessing the skill or inclination or patience to go farther, you’ve got a modern painting. It’ll be acclaimed and really sell in Beverly Hills. If you can proceed to the finish you’ll wind up with a realist painting. It’ll be dismissed as not really art, and wind up on eBay.”

I do accept, my dear professor Ted, that modern art as art and sometimes downright darn good art if not, to use the technical if capricious term, fine art. That is, if defined my way, a lonely way indeed, to a modernist an absolutely unacceptable way. Sounding for practical purposes like Robinson, I define modern art simply as simplicity as an end in itself, pared of all ideological baggage. Thus liberated my kind of modernism focuses simply on artistic principles, such as composition and coloration, which, carried to its logical apolitical extreme, is simply abstract, and that's fine.

Thus defined, and if I’ve closed my literal eyes to the posted modernist Artist’s Statement and the exhibition catalog, I could see Stella’s giant gently striated X or Claes Oldenburg’s 2-story clothespin as well crafted rather interesting decorative art, in the same league as an Art Deco stairwell, Disney's "Snow White," or Toys "R" Us. And your large decorative woodcut, Professor Ted, is exceptionally skillfully done, an award-winner, sir. Congratulations.

I've indulged in pure modern myself, notably in designing our modern redwood house in Ohio, ideally custom fitted to the Ohio woods but outrageously alien to the local hardly modern building culture. So anomalously modern was it that it was tough to find a builder to build it. As the filial of our septic tank bunker, I made a welded sculpture from ¼” rusted sheet iron, far too abstract for Henry Moore, as per my seascapist’s dictum (I didn’t know how to take it any further). My gala award was when a UPS man from Tennessee, with an accent as deeply Southern as our house was modern, just stood agape at the door, package frozen in his arms, and murmured, "ah HAY-yant NEV-ah SEEE-en NUTH-in LI-yak THEY-us!" O modern art, dear modern art! We're kin, distant kin but kin. O why did you have to go and turn yourself into a hate crime! Can't we all just get along?

Unapologetically I declare myself a realist, not a modernist. My style is WYSIWYG – What You See Is What You Get. Just by looking at anything in this gallery you should know what it is, and its message. I should think that telling you what your eyes see framed on the wall would be an insult to you, and your eyes. Of explanatory inscriptions that take you longer to read than to look at the painting, and more creative, you are spared.

I’m a realist, almost. I’m not a 70MP photo-realist. Not an academic brushstroke-free Beaugeaux realist, but a Sargent realist, a pre-decadent Impressionist-realist, a hyperkinetic bravura realist heavy on the impasto and palette knife and glazes. Realists of any era are famously as addicted to the color black as couch potatoes to beer. Couldn’t get along without it. But the pioneer Impressionists, in trying to recapitulate nature (a well-kept secret) cringed at the thought of black, and so do I. But modernists who claim pioneer impressionists as their DNA providers, love black, wallow in it.

To be fair and balanced, I acknowledge that when I tour a large, comprehensive art gallery I march on through the medieval and colonial American sections; pause just long enough in the 18th and 19th century French Art sections to chuckle at the kitsch (where is Thomas Kinkaid when we need him?) of a Fragonard and marvel at the technique of a Bouguereau; stop and seriously study from a right distance the optical trickery of the not-yet-degenerated, pioneering French Impressionists like Monet and Sisley who applied their daubs scientifically to magically enhance reality; take time out for lunch at the gallery café (kale with feta cheese salad, hold the cilantro); then advance to the American late 19th century and early 20th century and put my face right into the Thomas Dewings and Grant Woods; and finally linger in the Sargent-Zorn-Sorolla wing until closing time.

So I’m a WISIWIG-er (What I See Is What I Get). And I see shifting backlit clouds and shafts of light beaming through and creating light shows playing upon the comfortably rounded spring-green California grassy hills. I see reflected light from a blouse subtly modifying and enlivening the shadow cast by a chin, which is darker and more sharply outlined just at it’s origin as the jaw. If God created nature and man in it, and declared it good, it’s good enough to paint as my eye sees it. I contend that an ideal quality which art should glorify is beauty. That’s easy for me as a realist to say because I’m looking at real things with my real eyes, built to see a woman’s eyes as beautiful -- maybe enhanced a tad by the inner eye or Photoshop, both properly bridled. Meanwhile a Gopnik has decreed that a Mark Rothko is creative art worthy of SoHo and MoMa, while a Sargent isn’t even art, presentable only at garage sales or eBay.

Keats and his Romanticist eye had a point. Beholding a Grecian urn bearing a fine drawing he murmured poetically, “beauty is truth, truth beauty,” inexorably entwined. Inner-Eyed metamodernism owns ugliness; beauty is owned by literal-eyed realists.

So what I see is central to my art. What I see with the literal eye is what I feel. I see backlight clouds and hills and I feel an urge to, well, stand up and stretch out my hands and breath deeply, and sing – if I could. Inner-Eyed modernists do not have exclusive ownership of ebullience. It’s not their trademarked emotion. Even realists experience a kind of elation.

I need to qualify that. Modernists in their Statements and Manifestos hype their “highs”, expressed in some kind of wiggly rock movements, at least arm waving, and grunts and shouts, insisting they’ve just gone where no man has gone before, which for too many turns out to be a much trafficked rehab unit. I’ve never been there. I strive, no bones about it, to go where the Sargents went, and the Silvermans, Schmids, Carl Samsons, and Lauritzes, have gone.

Rather, what I feel, both gazing at backlit clouds and painting at my easel, is not so much ecstasy as “joy”, though highly tinctured with generic excitement. But it may be a very quiet and lonely sentiment more associated with the vocabularies of the KJV Bible and Oxford don than moony manifestos. At the easel, I'm so engrossed with getting the reflected light in a shadow under a chin or whether to mix white or complimentary color that only those technical questions come consciously to mind, and then faintly. I'm ... just doing it. There I go again, saying "I just do it." Not ecstatic, even joyous, or sensibly creative or inspired, oblivious of time or distractions, just totally channeled into the doing of it, getting it to happen. Otherwise thought-free. I can't describe it; there's nothing to be described. Nothing I could rhapsodize about in a Statement for a gallery wall. Could it be a little like falling in love or into nirvana, if nirvana is about which subtle tint to use and how thickly applied?

My own artistic joy is in, yes, just doing it, more in the doing of it than in the honor and fame and possible wealth that what I have done could bring. Thus even if my opus magnus, the over 70 oil portraits of the LLU faculty, be consigned to storage and boxes and seen only by my own inner eye and no literal eye, it remains for me my joy, just for having done it and for the memory of doing it, and the prospect of moving on to another canvas. I admit that I'm non-mainstream and that my reactions are quite different from those of normal people. I blame it on being an artist. Artists are odd. Anyway, I get no satisfaction from public praise, such as generic achievement awards and galas, of my painting. In fact it's rather an ordeal for me to sit through such an event; my mind wanders. By the same token I get even less satisfaction from legal action against recipients of donations of pictures who simply store them in a warehouse. What satisfies me most is simply painting and knowing it's good; also from winning a first award for a certain picture in a juried exhibition, and from seeing a donated series exhibited.

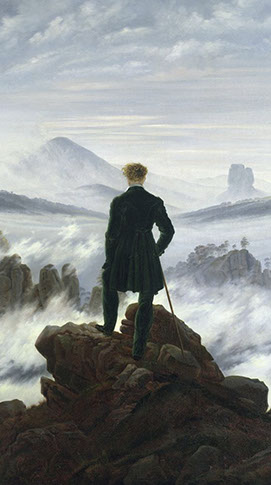

The romantics called the joy they experienced by looking at nature sublimity. The poster boy of sublimity is the “Wanderer Above The Mist,” a pain ting by the 19th century romantic painter Caspar Friedrich. Clad in frock coat, Caspar’s “Wanderer,” he’s just standing still, looking, looking, feeling and feeling…and posing – not beating his breast and bellowing or breaking into a rock dance.

ting by the 19th century romantic painter Caspar Friedrich. Clad in frock coat, Caspar’s “Wanderer,” he’s just standing still, looking, looking, feeling and feeling…and posing – not beating his breast and bellowing or breaking into a rock dance.

I reckon that of realist painters it is the landscapist, beholding scudding clouds and breaking waves and folded hills, who experiences the most sublime sublimity. Of non-modernists the landscapist can write the most soulful gallery Statements. But portraitists, which I wound up being, do also experience their own kind of indoor thrill upon contemplating a fold of jowl. Sargent did, at least as a young painter just starting out. Alas, after a career of it he famously sighed, “I paint no more mugs,” whereupon he went outside and painted landscapes, of which he never suffered angst. To me a head remains as exciting as a headland.

But for me when confronted by a sublime landscape it is not enough simply to stand there leaning against a walking stick, or, in my case, a cane. It’s got to be a brush. And I cannot just stand there, myself a picture of sublimity. Instead I must …do something.

Not altogether whimsically I suppose my urge is analogous to that of the bare foot maiden floating across the meadow gathering spring blossoms, or the hunter crouched at a quiet pond magical in the twilight with a v-formation of mallards against the golden sky. He simply must BANG them all dead. A real estate developer, beholding virginal green rolling hills, driven to survey and parcel it all, from east to west, and construct 3000 identical 3-bedroom FIOS ready houses, a dozen Walmarts and a constellation of Starbucks. Farmers of the several cultures would plant vast fields of soy beans, chardonnay grapevines, or marijuana; greeniks must cover the landscape with groves of 120-foot windmills and banks of solar panels; frackers must frack. Protesters must occupy the earth with forests of signs, megaphones, megadecibels drums, and dumpsterfuls of litter and paraphernalia; the EPA must regulate the eco and all that in it is; the Taliban will simply blow it up. Or if confused by pop-modernity, one simply stands and bellows.

But I, I must... I must consume, gulp, the scene as a sweeping whole, a panorama, the whole composition (not in detail; I’d make a terrible bird watcher). I must absorb it, open myself to it and take it all in like a python swallowing a rabbit whole – and then give it back. I must absorb it through my eyeballs and every pore of my skin and disgorge it all onto canvas, sometimes flailing my big brush. I'm a kinetic painter, like Sargent, or was before octogenariancy slowed me down. I hate picking at minute details with a wispy kolinsky sable brush, like a medieval painter. I try to give the impression of detail, as the Golden Age California landscapists did, or the pioneer Impressionists, only not restricting myself to daubs. Developed at the same time modernists were dispensing with any attempt at reality, this new realistic painting magic yields the perception of even greater and more natural detail than ever in history, certainly for landscapists.

Mercifully for the subjects (especially young females), when I paint a portrait or figure the urge to “consume” is less compelling than banal technical questions. Should I use a #4 sable or a #14 bristle? I usually grab the big bristle, not her.

I review my life in art and realize that I have over the years indeed developed my own philosophy of art, no thanks to a Ruskin or a modernist theorist, or any art appreciation course, or John Updike or Tom Wolfe (novelists who also effusively essayed framed art). And no thanks to Leo Tolstoy, another great novelist-artist presuming to theorize all art. In his his essay “What Is Art?” he proclaimed that “Art is not … the manifestation of some mysterious idea of beauty or God.” Yet perhaps Tolstoy turns out to best reflect my philosophy of art, by declaring the exact opposite of mine.

I owe my personal philosophy of art to this school, as it was 68 years ago, a small Bible College. And I took bible classes, not art.

Art is from and centers around God, who gave us all that is seen by the literal eye, and me the use of it, and the Inner Eye to boot. If wise men have declared it is art that gives escape from, and consolation for, calamity, capitalism, cops, and the human condition, and fills voids in our soul and fulfills the soul’s destiny, I say it is God who does all that, through, among so much else, art, which He created along with swans, constellations, and orchids, and me and you, dear gallery goer. For escape, consolation, beauty, and life, and art, He has promised to take us where no man has indeed ever gone before, which “eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, nor entered into the heart of man.”