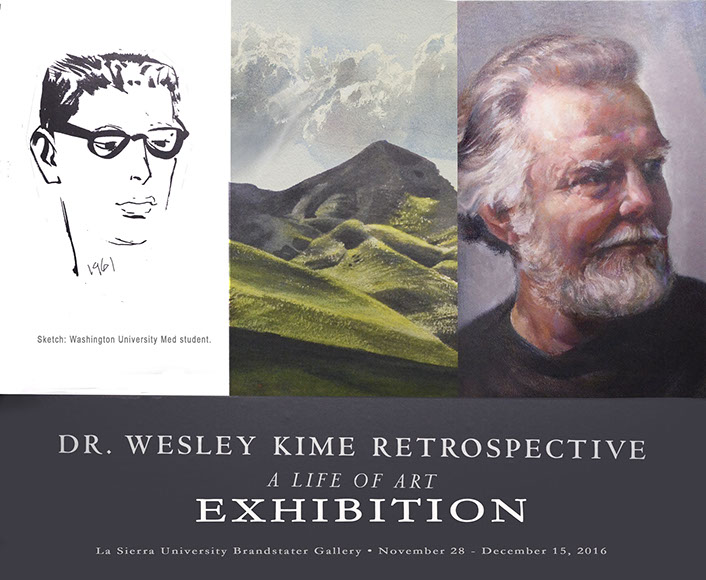

In my one-man retrospective, more fully described elsewhere, the following biography, duly written in the third person, was displayed on the Brandstater Gallery wall.

BIOGRAPHY: WESLEY KIME 1929 -

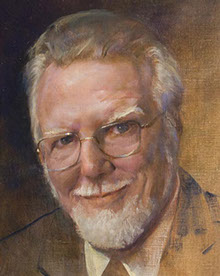

Heedless of the maxim, “no man can serve two masters,” Wesley Kime has pursued with equal faithfulness two demanding careers, medicine and art, rather as in biblical times a wife and a concubine, or as a circus juggler juggling an egg and iPod. It never came near divorce but neither did it quite work out as a marriage made in heaven. He never felt fully at home in either art or medicine or fully accepted in either. Sadly, though he yearned to be welcomed by the community of professional and schooled painters, even to the point of painting his self-portrait (shown in the poster) as a long-haired Bohemian rather than that Washington University Med student, that sentiment was largely unrequited. The painterly clique was less cordial than the medical, famous for its elitism. But he recoils at comparing his sense of alienation to that of a transgender.

And though he gave both his best, in his judgment he did not do the fullest justice by either. Kime suspects that nature gave him more potential in art than medicine. but although his art is superior as realist art to that of most even advanced hobbyists, as he trusts is evident in this exhibition, it is not, he decides squinting his trusty literal eye (the one remaining good one), quite of the quality he suspects he is capable of. Not quite world class. If he had been trained at, say, Ecole des Beaux Arts and studied under Carolus Duran instead of at a School of Medicine pursuing art under cover, and had always practiced art full time in an appreciative and equally artistic collegial setting, and had good agents to promote his oeuvre and name.

Art for him has been an uninterrupted life-long affair. Medicine was but a 50-year occupation that drove art underground. But art didn’t put up the storied fierce underground resistance as much as peaceful collaboration. After Kime had, at age 65, slammed the office door behind him, art at last came out of the closet and took over full-time. His career had been medicine; his life, art.

Kime’s mother, a girl from an impoverished Oklahoma farm, was talented in art and briefly took painting lessons (before Kime can remember) from Paul Lauritz, one of the then-active legendary Golden-Era California landscapists. Also interested in a great many other things besides painting, she had, by the time Kime remembers her, moved on. Besides an awe of Lauritz, her two main contributions to her son’s art were a library of advanced art texts and anthologies, which young Kime discovered and copied, and regular visits to the old L.A. Exposition Park, which at the time (the 1930s and ‘40s) was the one museum in town for everything from mummies to Lauritz.

In medicine Dr. Kime was trained to the gills, a total of 27 years in medicine or premedical. After the usual 12 years of elementary and high school,19 year’s worth of study dedicated to a medical career: college (Occidental College 1 semester, premed and 1 art course; this “Bible college,” BA, biology major, no art.) Then 15 more years: med school; army service at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology during its heyday; two separate specialty residencies (and board certifications) at USC, Harvard’s Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Washington University; a subspecialty research fellowship (renal physiology and disease), not to mention regular postgrad conventions and workshops. School over, he taught and lectured med students and residents all his career. But in art largely self-taught.

However, Kime did have a whiff of formal art school training at the teachable and invincible age of 23 at Otis Art Institute, a duly famous art school accredited for training professional artists. But, Kime acknowledges with a sigh, he was there only one quarter for a couple of night school classes set up for gas station attendants and housewives, not career artists. His day job was internship at the neighboring 3000-bed L.A. County General Hospital, where house staff duties were overarching and working conditions were later described as grueling and inhuman. At least as profitable as his token tour at Otis were DVD demonstration by Burt Silverman or Richard Schmid if studied a couple of hundred times while exercising on the treadmill, as Kime has.

Kime likes to say his de facto full four-year art school was his Medical school. He grades the school as A+ for handling a pen and pencil, F in charcoal which is standard in art schools but begrimes white coats. Quickie (45 minute) watercolor plein air painting can be worked into the schedule, but not the much more demanding and impossibly messy oil painting. Flailing a 3” brush at an easel in pharmacology class is awkward. Experience in sketching live heads is superior to formal art school but pathetic for full figures, and exposure to cadaver anatomy is unexcelled but wanting as Michelangeloean or superhero musculature. Medical school professors exist in a universe not even parallel to that of art, are innocent of art metaphysics, or Bohemian creativity and lifestyle, and are delighted to be used as role models, not sketching models.

Using shirt-pocket pens, on anything from lecture notes to the backs of Grand Rounds protocols, from paper towels to napkins at restaurants or tithe envelopes at church, or the palm of his hand or a tortilla shell as last resorts, drawing was the unbroken thread of Kime’s life in art. Starting in toddlerhood before he can remember and never stopping even as other little boys advanced to more mature things like girls and tether ball, sketching continued and burgeoned during medical school and the practice of medicine, and tapered in old age, coming to a halt just a few months ago thanks to a cataract in his remaining good eye (the other eye had long been legally blind because of macular degeneration). Flash cataract surgery is scheduled.

Preschool and early school-age drawings were detailed copies of everything from art deco wood-ducks from Applied Art by Loomis to advanced Art Anatomy from The Human Figure by Vanderpoel. Starting around the 5th or 6th grade, rather than gazing out the windows at things seen only by his inner eye like winged dragons and Spanish galleons manned by mermaids, as arty kids are expected to do, he gazed at what he could see with his eyes. Medicine would put him under lifetime house arrest, so to speak, where he would see only people, for his purposes only their faces.

Drawing faces came to take on a happy life of its own. Whether classmates or pew-mates, anybody in the same room, whether classroom, church, or tortilla parlor, served as unposed, unwitting, not infrequently dozing, or frowning, subjects.

At first detailed, blocked in, and belabored in the full classical academic manner, these sketches of necessity, considering the restlessness of his unwitting models, became 15-90-second flashes, fearlessly snapped flourishes materializing as “that’s him!” faces. Kime says G.K. Chesterson, a theologian writing about art, best describes his flash sketches as “art, like morality, is drawing the line somewhere.” All together Kime supposes he has done – a very rough guess – 10-20,000 people sketches, pitched unsorted into cardboard boxes.

Kime didn’t flash-sketch classmates just to flash his work to everybody to flaunt his odd talent. Kime liked to think no one suspected that his pen was yielding other than doodles, which in such a soporific setting was countenanced. Never once did a professor or committee chairman tell him to knock it off and pay attention, or even frown, nor did a classmate giggle. Much later Kime liked to quote Andy Warhol, whimsically out of context, “Art is what you can get away with” in Tumor Board.

Early on, Kime himself dismissed his drawings in class as only doodlings. Then he saw sketching as preparation for the full easel oil portraits he would do … some day. Recently when Curator Ted recognized Kime’s sketches as ends in themselves and devoted a whole wall to featuring an aliquot of them, Kime’s first reaction was disappointment that his magnificent framed oil seascapes weren’t hung there instead. But then Kime began to comprehend Ted’s curatorial insight. Thanks to Ted, Kime realized that if not classed with the finished pen drawings of a Dana Gibson, his 15-second works could well be among the best in the annals of art.

Unposed, unwitting people have not been his only subjects. He has had two periods of drawing or painting professional posed live models. The first was at age 13 or 14, in North Hollywood where he grew up. At that time Hollywood studio artists were abundant and would get together in evenings and hire models, clothed in deference to young Kime. Also, young Kime had advanced only to charcoals. The other was in his 70s, when his oil painting phase was in full swing, at the Cincinnati Art Club. Lots of nude models. But by then the very old man had become enamored of faces and shrugged off the chance to paint the rest.

His lifetime of flash line sketching rendered him both better and more poorly prepared for formal portrait painting than art school-trained professionals. Better by being so swift. At the CAC he could dash off rather finished and creditable portrait and be out of there by the 2nd break. And better able to catch the quintessence of the model and fleeting nuances of expression that distinguished that particular person from all others. But the breakneck speed of flash sketching introduces the danger of their falling into frank caricature, disadvantageous in achieving flattery, as rich portraitists must.

At any rate Kime’s delayed full-blast oil painting phase endured for nearly 30 years and yielded over 500 paintings, notably portraits but also seascapes. He considers the magnum opus of his whole life in art a series of 70 oil portraits of the LLU faculty, a 15-year project, unlike that possessed by any other medical school. He has been called the portraitist laureate of LLU.

In both medicine and art Kime has received the usual ration of awards. In medicine several “Teacher of The Year” awards. His alumni association set up a special “Iner S. Ritchie” award just to honor Kime’s contribution to his medical school through his series of faculty portraits, and, Kime chuckles, to acknowledge his moxie in juggling both fields. Presented at galas and banquets, these he accepted with dispassionate humility bordering on indifference.

Those he received in art somehow meant more to him. The doctor won 5 consecutive Art Club Sketch Group blue ribbons in 6 years, beating out his retired art-school easel-mates, embarrassing him to the point that he considered disqualifying himself from further competition. But he won only 2nd place for Seascapes in International Artist; a modernist abstraction won 1st place.

But the present one-man exhibition of actual paintings in an actual gallery complete with reception with a token tray of Coca Cola and neatly arranged chips of cheddar cheese, is, he exclaims dabbing at a tear, the absolute most overwhelming award possible. Even without brie, cauliflower and chardonnay, the exhibition is, he proclaims, the crowning event of his life in art. Chardonnay, even cauliflower, aren't, he acknowledges, his prevailing values anyway.

“Are you sorry you took medicine?” the doctor is often asked. Absolutely not! Medicine, certainly the study of medicine as a science, especially biochemistry, and embryology, genetics was even more exhilarating than the color wheel and the Golden Ratio. But to fully live medicine, a physician must love to heal people. To my regret, it turned out that what I loved about patients was sketching them, sometimes while I was taking their medical history.” The conversation often ends like this: “Oh but you’re so lucky to have such a relaxing hobby as art. My great grandmother, she paints too.”

That’s nice.

To conclude his biography, Kime says, “If my life in art began before I can remember, it begins to end as I begin to forget. If in youth I couldn’t explain why I painted, and could only say that I just did it and that's that, in old age I cannot explain why I don’t. I just don’t. And that's that. Whatever muse or spirit was within me that compelled me to paint is gone. Old age robs a man of most everything. That's the bad news. The good news is that I'm finding that being almost 89 paradoxically and unexpectedly and happily also has robbed me of interest in being robbed. I feel my interest turning elsewhere, mounting upwards, which is as exciting as gazing upon a sublime earth-bound landscape.”

Then the doctor, with that old grin of his, reminds us that old artists never die, they just scumble away.